Wer mit Ungeheuern kämpft, mag zusehn, daß er nicht dabei zum Ungeheuer wird. Und wenn du lange in einen Abgrund blickst, blickt der Abgrund auch in dich hinein.

He who fights the monster should be careful lest he thereby becomes a monster.

And if thou gaze long into an abyss, the abyss will gaze into thee.

Frederick Nietzsche, Beyond Good and Evil.

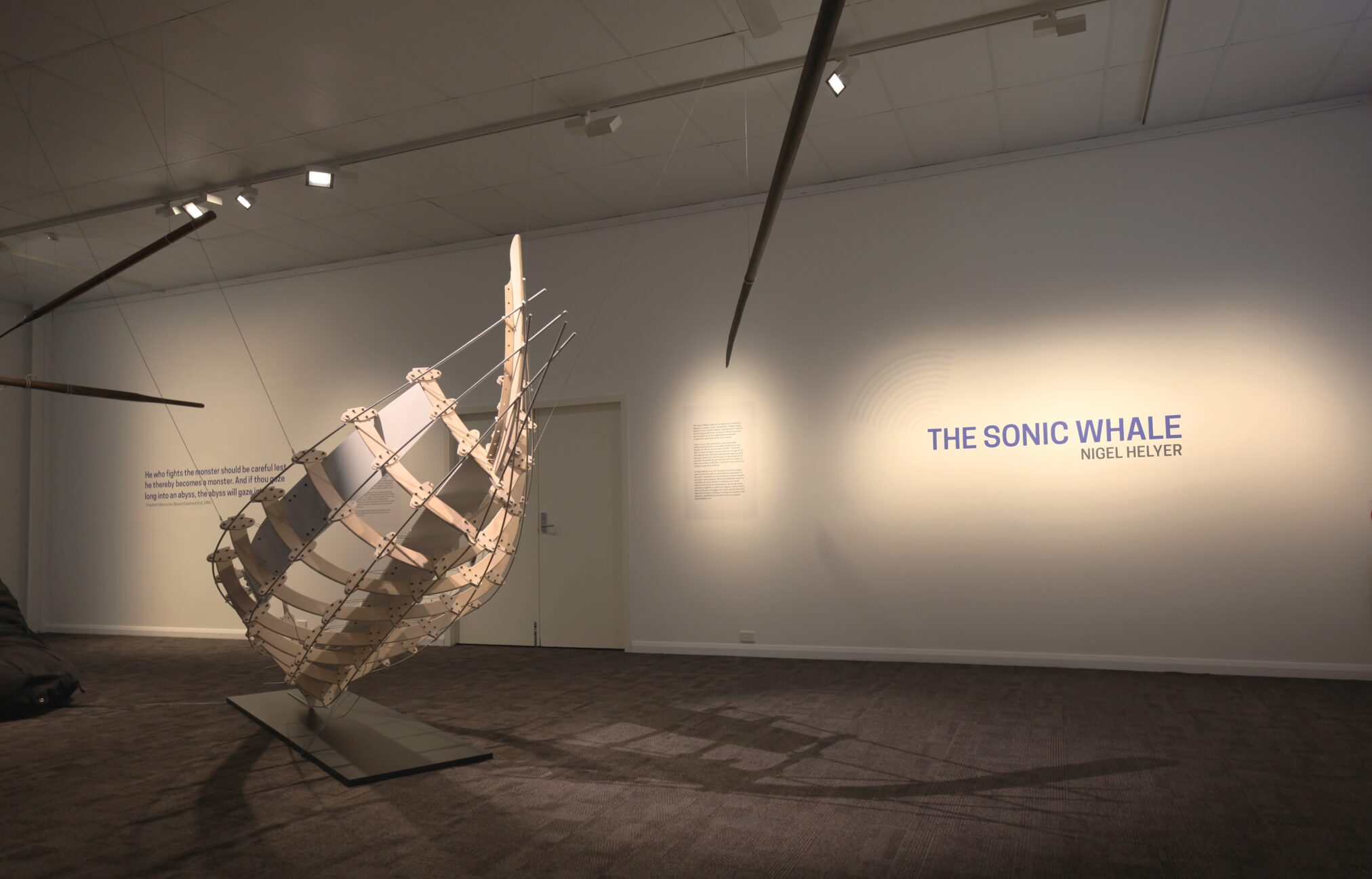

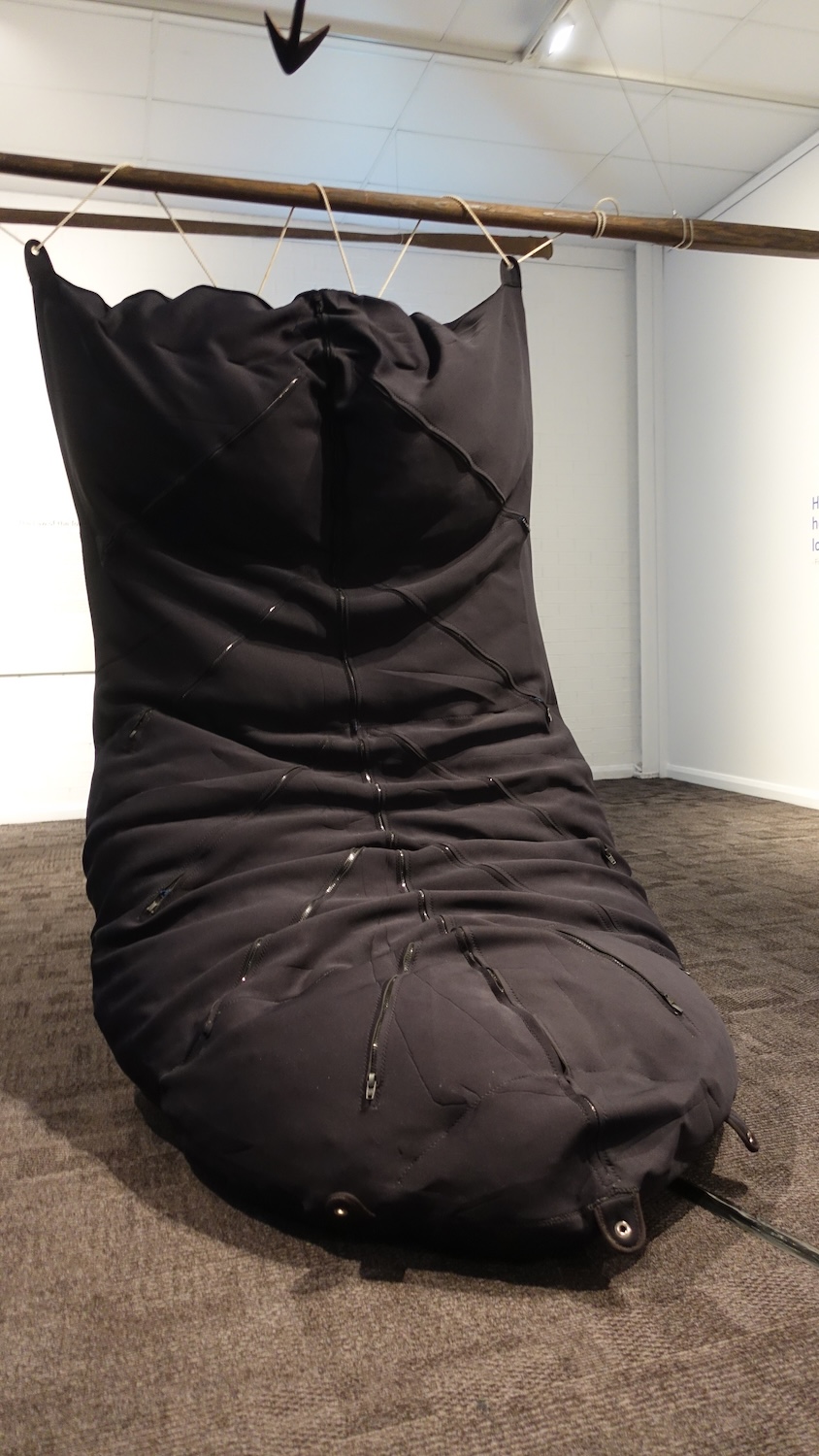

The Sonic Whale explores the delicate connections between humans, orcas, and whales: relationships built on trust, mutual respect, and betrayal. It reflects on the impact of human actions on these creatures and reminds us of the fragile balance between cooperation and exploitation in our world.

A key story in this exhibition is the remarkable relationship between orcas (killer whales) and the whalers of the far south coast of NSW. Combining efforts they worked to harass and hunt the giants of the deep as they followed their annual migration path between Antarctica and the warm tropical waters of northern Australia. Human betrayal and the death of the orca, known as Old Tom, resulted in the end of this unique cooperative alliance.

Highly evolved sonic beings, whales experience the ocean primarily through sound. Echolocation guides their migration, communication, and hunting. But this deep reliance has made them vulnerable in a world increasingly saturated by human-made noise. In 1946, British whaling ships were outfitted with wartime sonar originally developed to detect submarines but repurposed as ultrasonic nets to track and hunt whales.

Today, that militarization continues beneath the surface. The US Navy’s use of mid and low-frequency active sonar—capable of traveling hundreds of miles underwater—has sparked fierce legal and ethical battles. Despite mounting evidence that such sonar devastates whales’ inner ears, cripples their navigation and leads to mass strandings and deaths, courts have upheld its use. In an ironic twist, Japanese factory whaling ships have adopted US military Long Range Acoustic Devices (LRADs) as weapons—not against whales, but against those trying to protect them. In 2009, activists aboard marine conservation vessels faced blasts of high-intensity sound designed to cause pain, disorientation, and permanent hearing loss.

As technology reshapes marine soundscapes, we are left to consider: who owns the ocean’s silence, and at what cost?

Killer Whales: echoes of a unique bond

Killer whales, or orca (Orcinus orca), are sonic hunters, using echolocation to locate and identify prey. By emitting high-frequency clicks that bounce off the underwater environment, the returning echoes allow them to “see” with sound, sensing size, shape, and movement even in dark or murky waters.

The Yuin people of Twofold Bay near Eden, NSW, shared a deep spiritual bond with orcas calling them Beowa, meaning brother or kin. Believed to be their ancestors reborn, Yuin people sang to them for protection and food which orca would provide by herding baleen whales ashore.

From the 1860s, a pod of orcas formed a symbiotic partnership with the Davidson family who practiced small-scale whaling. Each year, orca would swim into the mouth of the Kiah River and tail-lob—called “flop-tailing” by the Davidsons—to summon the whalers and guide them to where a hunt was taking place. On dark nights, crews followed the glowing trails of bioluminescence stirred by the orcas through the water.

Orca would drive prey into the shallows and even bite down on harpoon lines to stop whales from diving. Once the whale was killed, the orcas took only the tongue and lips—leaving the rest for the whalers. This interspecies agreement was known as The Law of the Tongue.

This bond extended to protection, with whalers rescuing entangled orcas, and orcas defending whalers from sharks when boats were overturned. This trust was shattered in 1923, when a town vagrant killed a beached orca. The mourning orca left for the remainder of the season and in the following years, fewer orca returned to participate in the hunt. Old Tom, the last of the Eden orcas, died in 1930. His skeleton, still showing teeth worn down from restraining whales, remains a powerful reminder of a rare and respectful collaboration between humans and the wild.

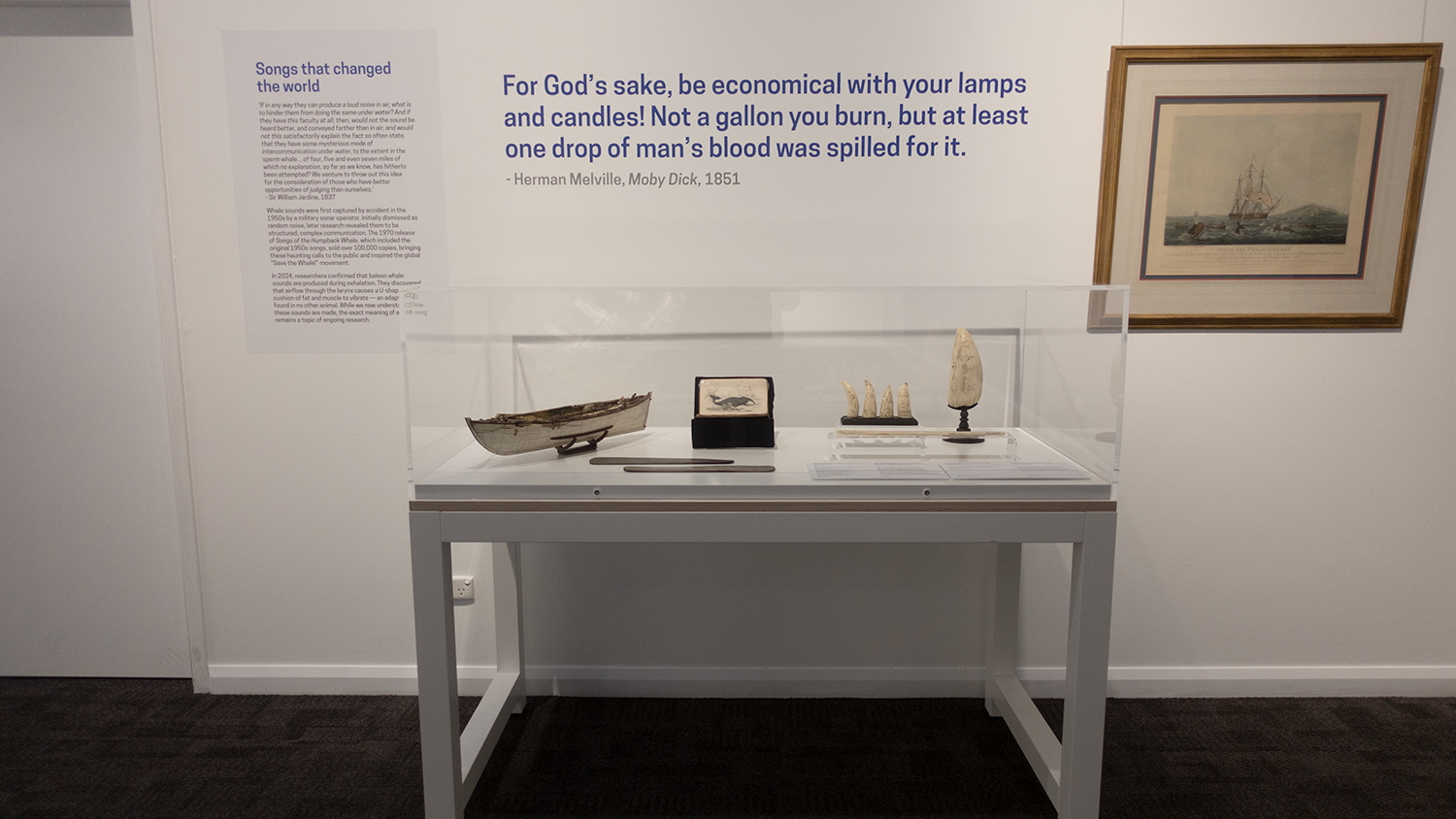

A History of Whaling: global and Australian perspectives

For centuries, whales were hunted across the globe for their valuable resources. Whale oil lit lamps and lubricated machinery; baleen (also called whalebone) was used in corsets, umbrellas, and brushes; and meat fed communities and markets.

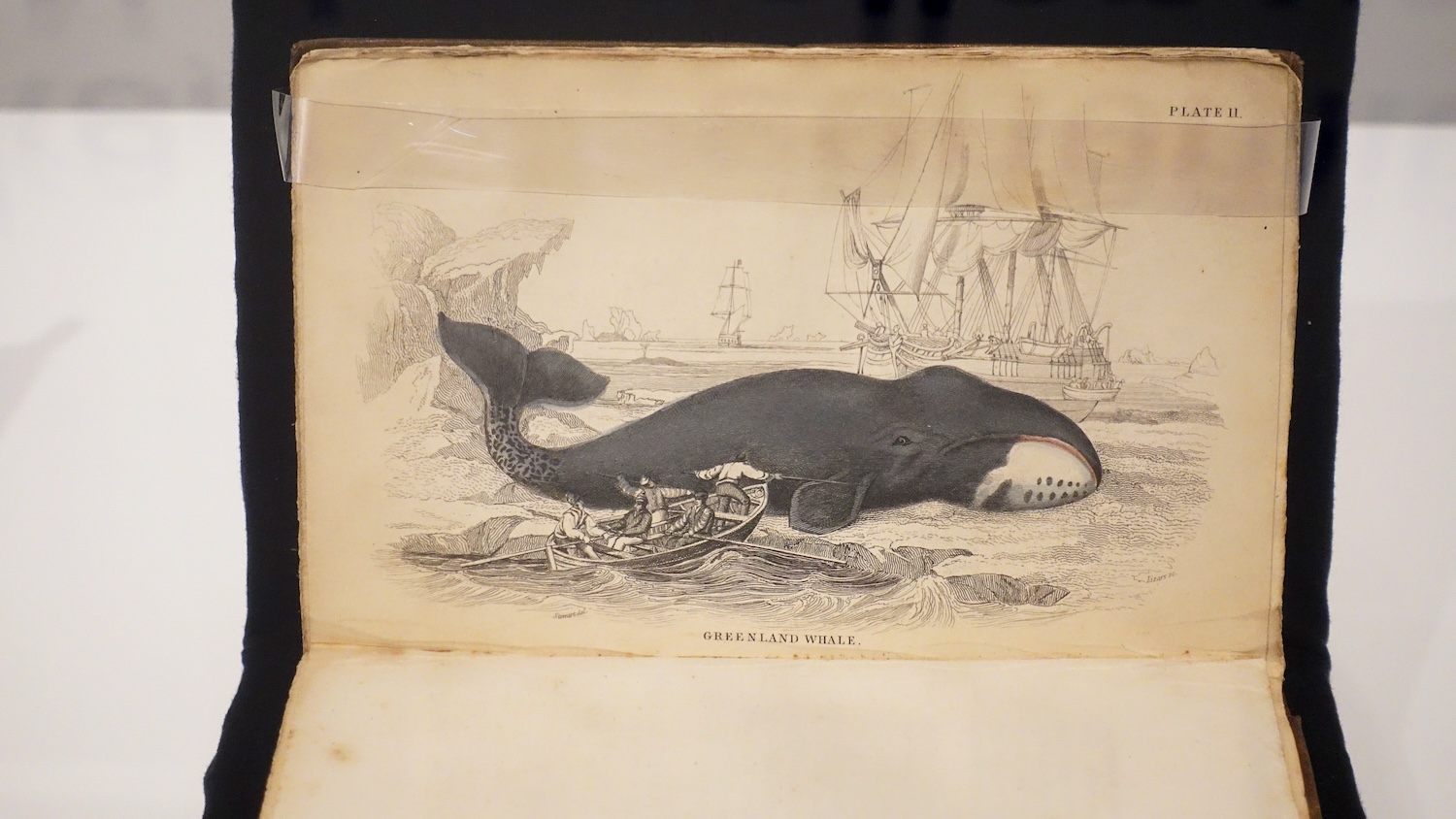

International commercialised whaling began in earnest in the 17th century, driven by European and American demand. As maritime technologies advanced, catches increased—but so did the toll on whale populations, pushing many species toward extinction.

In Australia, shore-based whaling began in the late 1700s, shortly after European colonisation. Early operations – such as at Jervis Bay and Eden – relied on lookouts to spot migrating whales, which were then hunted from small boats and processed on land. Over time, declining whale numbers and changing economic priorities led to the industry’s collapse.

The Sea and superstition go hand in hand. For centuries sailors unwittingly sensing the song of the Whale through their wooden-hulled ships thought them Ghosts of the deep and despite the thousands of close encounters in the Whale hunt they remained ‘mute’ until the middle of the 20th Century.

The accidental recording of humpback whale songs recorded by the military sonar operators in the 1950s, combined with the groundbreaking research of biologist Dr Roger Payne, sparked public interest in whale communication. In 1970, Payne’s album The Song of the Humpback Whale sold millions of copies, changed how people viewed these creatures. The public began to understand the emotional complexity and intelligence of whales, which helped fuel the movement to end whaling. Australia’s last whaling station (Albany, WA) closed in 1978. That same year, Australia shifted from a whaling nation to a strong advocate for whale conservation, playing a leading role in establishing the Southern Ocean Whale Sanctuary.

The Sonic Whale is on exhibition at the Jervis Bay Maritime Museum from August 2025 until February 2026. It is a development of The Law of the Tongue originally commissioned by the Aboa Vetus & Art Nova Museum, Turku, Finland (2010) and subsequently exhibited at the Gallery of the American University of Sharjah, UAE, as part of the International Symposium on Electronic Arts (ISEA 2015).