A short speech written and spoken by Gary Warner at the invitation of the authors for the book launch of Culturescape: An Ecology of Bundanon by Nigel Helyer and John Potts, at the Australia Council, Pyrmont, Sydney, Thursday 30 January 2020.

This edition is now available online at The Bundanon Trust site.

At Bundanon:

Spotting a young fox gambolling across a cow paddock at dawn – long grass, swirling mist, icy air – a cute little bushy-tailed monster.

Watching a grey fantail’s calligraphic flights, chasing insects against the sun; and swooping down to drink from rainwater at the base of a tall spotted gum tree.

Listening to the chitter of welcome swallows perched on power lines, briefly resting between cycles of collecting and depositing mouthfuls of mud on the just-so walls of their developing nests under the eaves of the concrete-walled art storeroom.

Woken by the improbably loud, guttural grunting & groaning & crashing about of wombats quarrelling at midnight in the crawlspace under the sleeping quarters.

The distinctive pain of being stung on the calf by a bull ant, & putting into practice a bush medicine tip of breaking open a bracken fern stem to rub on the quickly swelling and reddening skin, for welcome relief.

Watching in awe as Rea’s MAANG ceremony unfolds in the night – a huge shadow drawing of a word from her Gamilliray language being firestick burnt into a paddock near the homestead.

Seeing an orderly queue of eastern grey kangaroos lined up at dawn to scrunch one-by-one under the paddock fencing at one of their well worn self-made access points.

Watching the hulking form of Elvis the black Angus bull sleeping under a full moon in his isolation paddock.

Listening to the aeolian drone as a strong wind pulls an air column up the solid stone chimney in the single room single man’s hut.

Sitting on the lawn listening to the late Jim Wallis unreel threads from long, deep skeins of knowledge, of plants, place and practice.

Standing at a small desk in front of a window of the Musicians cottage on a gorgeous morning, embodying a practice of John Cage, late in his life, in residency at crown point press making drawings and prints by tracing the forms of found river stones. And in the evenings making recordings with spinning bric-a-brac, and bouncing superballs inside the Steinway piano – stumbling along the way of that joyful sensei.

Trying to sit quietly in leaf litter, peering through foliage to watch an indigo-black male satin bowerbird dance around and through his immaculate bower, loudly singing his whirring metallic rhythms. He’s at least seven years old because that’s how long it is before a male moults to this colour.

After dusk, watching in quiet amazement with an assembled audience on a sandy beach of the Shoalhaven. Tess de Quincey glides past, illuminated, in the middle of the river, effortlessly standing on its surface, dancing her slow butoh. Improvised acoustic music is floating in the air, flowing with the river in the night – invisible forces at play.

Audio-recording my footsteps pacing up and down the wooden verandah outside Arthur Boyd’s painting studio, on an afternoon of heavy rain.

Getting lost on the forest ridges, on a ritualistic no-tracks walking between Bundanon and Riversdale, with the brilliant Nick Keys. Both of us, at a massive assembly of huge boulders, covered in orchids, lichens and lithophytes, having that sudden strong feeling of prior human presence.

Having an ‘Aaah…’ moment walking into the sitting room of the homestead to experience Nigel Helyer’s Milk and Honey installation, thinking ‘now that’s the way to use those induction transducers! activating wooden objects by making them sound – fantastic!’. I had done this for a single speaker sound work embedded in Fiona Hall’s Grove permanently installed in Adelaide’s Museum of Economic Botany, but here was a sharply realised combinative multiplicity of instances, each sonifying a different, conceptually powerful object, each a different sound source, activating the already strong installation presence, and the room, with a beautiful melancholic poiesis of song, spoken word and field recording.

Like many people in this room, I’ve been experiencing Nigel Helyer’s sonic-kinetic sculptures since the 1980s and have always been inspired by his artistic ambition, collaborative methodology, his choice of materials, his attention to the details of design and construction, and his ability to explore, adapt and incorporate ideas – be they current or classical – from the realms of science, art, poetry and many other domains and sub-disciplines.

Like Nigel, I’ve spent precious times over many years at Bundanon – in and around the residency compound and the homestead, in the forest, by the river, on and off the paths, making drawings, making field recordings at all hours of day and night. And like him, I’ve sometimes used those recordings in talismanic return to the place through sound-art installations.

Which is to say, I have some empathic embodied experiential appreciation for Nigel’s use of sound – what it takes to collect and work with it – and always appreciate the ways in which he uses the medium, in the service of art, to shape temporal engagement in place; to prepare conditions for contextualised experience.

So I was humbled to be asked to speak tonight, to say something at this punctive moment in his, and John Pott’s, and Mark Taylor’s project Culturescape: An Ecology of Bundanon.

The project is a broad discursive conglomerate of influences, discoveries, voices; of scientific and anecdotal observations, tangents of history, conjectures and explorations. And one of its manifestations is the book being launched tonight, which is more than only a good read – it’s also a portal to a homestead in cyberspace, an immaterial residence for associated time-based media, documentation, reference papers, expositions and testimonies. For example, it houses the three ABC radio national podcast programs that punctuated thee are l three-year research project.

Importantly, the home page presents the interactive geo-spectral portrait-of-place at the heart of this entire project. Here, the visitor can explore a beguiling sonification of the elemental composition of soil samples taken by scientist Dr Mark Taylor and students at many locations on the Bundanon property.

The address of this homestead – culturescape.net.au – is referenced here and there throughout the book, prompting the reader to explore further, differently.

It’s interesting for example to allow the slow-paced elemental soil sonifications to loop as ambient music to accompany the book’s reading, shifting location occasionally to bump over to another variation.

And, here’s a gentle trigger warning – this book contains sentences such as:

“Soil samples were tested for 53 trace elements via an acid digest for total metals using inductively coupled mass spectrometry.”

and

“The King sits, and birds peck at his head.”

This slim and handsome publication comprises five chapters, punctuated and enhanced by a carefully selected procession of cogent images, all of which deserve their thousand words or more. But there’s no time for such an exhaustive recitation tonight.

The photo on Page 61, for example, provoked a couple of pages of ranty notes, phone calls with colleagues from the ’90s and rabbit-hole online searches before I decided that burrow was too deep and too well trammelled to traverse tonight. But I will, for the next few minutes, ramble a little along and around the book’s first three images, by way of exploration of some of the threads of discourse pursued in the text.

For me, these first three pictures, ping three different visual registers. The first is a technical drawing; the second represents the objective evidentiary – it is a photograph; the third is subjective expressive communication – it is a painting, a work of art.

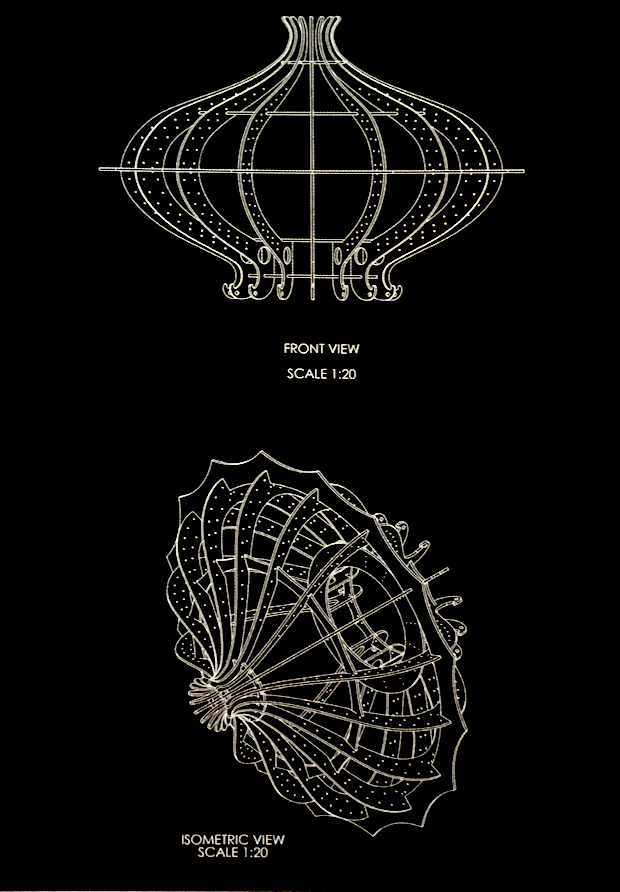

The first image we see in the book is a monochrome technical drawing of a yet-to-be object, a sculpture imagined and as yet only realised virtually as data. It is a CAD image, an image of Computer-Aided Design for one of Nigel’s characteristic biomorphic architectural sculptures. The image is a paragon of precision, definition, certainty. A curvaceous pleasingly symmetrical form with immediate appeal, this drawing is a promise to the future.

It is a drawing that is at once of our cybernotic time but at the same time oddly redolent of 19th-century pen and ink patent drawings for all kinds of novel inventions visually described in intimate detail.

Despite its utilitarian function, it is nonetheless a beautiful and slightly uncanny image oscillating between futurist promise and nostalgic sigh. It is illustrative of the work of the contemporary artist who labours at the interface of art, science and technology.

The second image is a double-page spread aerial photograph of the Bundanon environs. It is a type of image we’ve become so familiar with – the panoptic drones-eye view, perpendicular to the surface of the earth, revelatory of spatial arrangement, proximities, diagnostic textures and patterns. For those who terrestrially know Bundanon, the photo is a little puzzle – we try to locate ourselves in a place that we might recognise, down on the ground.

Two dominant lines bisect this photographic image. A dark meandering band widens appreciably as it transits from left to right across the two pages – west to east in cardinal orientation. Touching each edge, this is the strong ambulatory line of the Shoalhaven River. So like the body of a searching cosmological snake, it is an outcome of water’s deep-time power to find its way across and through the land, hugging the lowland, levelling where imperative, moving, carrying, depositing obstacles and particles. Water forms a river autonomously pushing onward to the sea at the continental perimeter.

The other line runs from bottom to top – south to north. Crossing the Shoalhaven waters once, it comprises two dead-straight theodolite-projected lines meeting at a shallow angle. This is a line of economy, efficiency, human agency and engineering. It is an easement, supporting power supply infrastructure that doesn’t flow IN the landscape but cuts directly across it, in a shaving away of the botanical hair on the earth’s skin. If pushed to concession, we might consider it a linear meadow, but it is an empty furrow through the forest, a technological holloway.

One of these lines is a drawing IN and the other a drawing ON the land. Read as a simple photo, the image offers an ordinary sense of the environs of the project. Read as a drawing, it provides an insight into the project’s subject – an exploration of hidden-in-plain-sight traces and residues of human occupation of this place – a weaving together of things bendy and things undeviating.

The third image is a small reproduction of an Australian painting. We might say an iconic Australian painting, certainly a painting by an iconic Australian painter. The 1978 painting is by Arthur Boyd, and he titled it A pond for Narcissus with Lillypilly trees. It is an expression of encounter with the bush, of being in the bush. It pictures a forest glade with overhanging trees and a calm pool of rainwater reflecting surrounding trees and sky. It evokes a familiar feeling of cool shade, of seclusion in the assertive indifference of nature to human concerns. Here is a place for self-reflection, where time slows or temporarily evaporates.

It is a painting of place represented by a relatively small volume of space, a container of sorts with shallow spatial depth but evocative of the surrounding space beyond the frame that’s been walked through to arrive at this arresting resting place, where a decision was made to hold this stillness in image.

This painting is art of a classical bent. It is a response to, a picturing of, the making of a memento of moment. Importantly for our considerations tonight, it is a silent holding of mercurial sensory experience, of the body in space-time. Prepared with the physical stuff of paint, it is a gift to the future.

Leading on from this enduring stratagem of oil painting, this book Culturescape: An Ecology of Bundanon charts a trajectory of creative evolution, along and into a series of innovative polymedia works of contemporary art conceived and executed by Nigel Helyer and his collaborators at Bundanon and Riversdale. The projects range from direct response to the paintings of Arthur Boyd, as in Bio-Pod V02; to the whimsical arboreal intervention of A Dissimulation of Birds; to the extraordinary Heavy Metal that visualises and sonifies the elemental constituents of Boyd’s oil paint, the stuff of his life as a painter, and perhaps, as the text postulates, the stuff of his mortal conclusion.

These and the other works presented in this book are a catalogue of conceptual provocations offered by the artist and the research team to the world. Alongside the work of the imagination and the necessity of creativity and personal determination, this practice of presentation is another correspondence between the lives of the artist, the writer & the scientist. All present their work – by exhibition or publication – to peer review and ultimately to the anonymous review of the crowd, to the public-now and the public-then where it will be experienced, and used, in ways unknown and unpredictable.

Like Thomas Biddulph’s 19th-century diaries of Shoalhaven life, Arthur Boyd’s paintings, Nigel’s polyvalent installations and sculptures, Mark Taylor’s scientific papers, and this new book by Nigel Helyer and John Potts, what we create is what we gift to the future we cannot know, as evidence each of our brief encounter with existence.

Gary Warner

Sydney/Gadigal land

30 January 2020

__________________________________________________________________________

Leave a Reply

You must be logged in to post a comment.